WARNING: I am inexperienced and not knowledgeable of computer architecture. Although noted below, I will be making a claim for a simplistic computer architecture that is not easily reproducible. The blog does not have data to back up my claim. I probably will regret publishing this post. We shall see how long it stays up. In the meantime, feel free to give corrections and criticism by opening a github issue.

I got bored so skimmed through the first few sections of Ulrich’s paper What Every Programmer Should Know About Memory, a gigantic paper about computer memory that I only took a small glimpse over the years. What ignited this post was the following:

It is therefore good for performance and scalability if the memory needed by the page table trees is as small as possible. The ideal case for this is to place the used memory close together in the virtual address space; the actual physical addresses used do not matter – What Every Programmer Should Know About Memory

Notice 1: I am still very new in the subject of system performance and computer architecture so please do raise a Github Issue if there is anything plainly wrong about my findings.

If you have taken a course in operating system or had an opportunity to work with memory at a low level, you will know that although two virtual address may be close virtually, they could be mapped to very different physical pages where the data is actually stored. Hence, my confusion. I was initially confused as to how programmers can exploit spatial locality if the data could be stored in different physical pages. While I do not know the full picture, I do have some ideas after spending a bit of time reading resources online such as OSTEP, a free operating system textbook, and recalling what I Have learned in the past. There are a few things I will be exploring:

- My interpretation of the quote from What Every Programmer Should Know About Memory

- The relationship with TLB, CPU cache, and cacheline

- The expected growth of TLB misses vs cache miss

1. Physical and Virtual Pages

As one may already be aware, memory is partitioned into fixed size pages. Although you could configure to have some pages to be large from my memory, let’s ignore this case. There are various reasons to split memory into pages and this is analogous to how we split files into fixed blocks. One reason is to avoid external fragmentation so that we can ensure not memory is wasted (though we could have internal fragmentation). Modern OS utilizes multi-level page tables which allows us to address more memory while saving space as linear page tables requires a lot of space (and each process requires its own page table). To give the illusion of memory being contiguous, the virtual pages are contiguous but in reality map to very different and perhaps fragmented physical pages (i.e. not contiguous at all). However, there is two traits that the virtual and physical pages share in common:

- The size of the virtual and physical pages have the same size

- Since both virtual and physical pages have the same size, the offset of the memory being addressed are the same

We can also verify this on our own system:

$ grep -i pagesize /proc/self/smaps | sort | uniq

KernelPageSize: 4 kB

MMUPageSize: 4 kB

We see that both the virtual and physical pages are 4kB which is typical in most 64-bit systems. Recall that the purpose of the MMU is to translate virtual addresses to physical addresses and page tables store page table entries (PTE) which contains metadata about the page such as if the page is in memory, if it’s writable and etc. Virtual addresses can be broken into segments that represents the indices of the different levels of the page table and the offset within the page. For instance, a page table could look like the following:

+--------------- VPN -----------------+

| |

V V

63 47 38 29 20 11 0

+---------+------+------+------+------+-----------+

| UNUSED | L4 | L3 | L2 | L1 | offset |

+---------+------+------+------+------+-----------+

|9 bits|9 bits|9 bits|9 bits| 12 bits

Once the PTE is found through the page walk, one could compute the physical address by:

(PTE.PFN << shift) + offset = (Address of Physical Page) + offset

Although I am not sure if this calculation is correct, for the intent of what I want to discuss, this math shall be suffice. What I want to highlight is that we need to know two things:

- the physical frame number (PFN)

- the offset

For simplicity, we could view the physical address translation as:

physical address = pagetable[VPN] * page_size + offset

Note: I want to stress that the math may not be entirely correct and is a simiplified view

Conclusion: My interpretation of the quote: the actual physical addresses used do not matter doesn’t downplay the importance of spatial

locality in physical memory but rather to refer that the fact that we will see a performance increase during the address translation phase.

I totally misread the quote and thought the author was referring that spatial locality didn’t matter. A common theme I have is misreading and

misinterpreting what I read … something I need to work on more. Though I could be wrong so feel free to report an error in my thinking on

Report a Bug link below the tags associated with the post.

2. TLB, CPU Cache, and Cacheline

TLB (Translation Lookaside Buffer) is a cache that the MMU (memory management unit) uses to avoid performing a page walk. TLB only contains the PTE and not the page itself. Parts of the page could be cached into the CPU cache. When retrieving data from the main memory, the fetch request does not only grab the data itself but a line of data referred as a cacheline. On a 64-bit CPU, 64 bytes of data are retrieved for each fetch requests and stored into cache.

Note: I recently learned there are a few different levels of TLB and TLB could be also split into memory and instruction just like CPU caches

Let’s suppose we want to fetch an element in an array such as an integer arr[0]. The CPU will also grab 15 other integers

(assuming an integer is 4 Bytes and our CPU is 64-bit) due to how the CPU fetches data from the main memory. When the CPU wants to fetch some

data from main memory, it’ll grab a chunk of data called a cache line into the CPU cache to reduce the number of times the CPU needs to access

the main memory because accessing data from main memory is EXPENSIVE. So if arr[0] was not in cache, we will have a cache miss and therefore,

the CPU will need to fetch arr[0] from main memory (or worse, it’ll fetch the data from storage like the harddrive to memory and then to cache).

It’ll also bring along arr[1], arr[2], ..., arr[15] along with it so that if we ever need to access any of the first 16 elements of the array,

we don’t ever need to travel to the main memory which is far from the CPU as it will already be in our cache which requires very little CPU

cycles to retrieve the data. From my understanding, CPU designers noticed that neighboring data are more likely to be access such as via a loop.

We call this type of access as spatial locality.

Note: while in theory, 16 integers should be retrievable from one request (should be 8 bytes at a time in 8 bursts to service the request in general), I am not knowledgeable if there are some caveats such as alignment issues and other factors. As I did not study engineering (in fact I am studying Mathematics which is far from this subject), my knowledge of hardware is limited

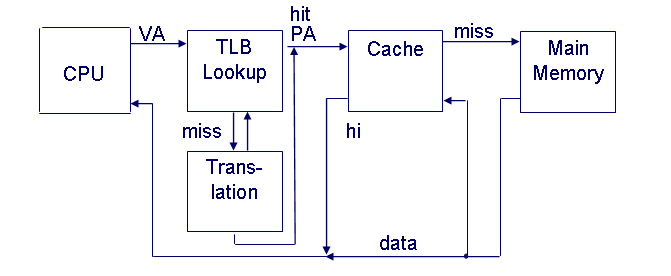

But you may be confused as I was about how the TLB and cache relate to each other. Recall TLB stores PTEs and cache stores data from the page. We first need to translate the virtual address into physical before we proceed to fetch the data. If the PTE is already in TLB, then there is no need to do a page table walk, but we may still need to fetch the data if it’s not in the CPU cache. The PTE can be used to retrieve the data from the main memory if the data is not already in cache. The diagram below does a good job to capture this relation:

A high-level illustration of how data is retrieved which makes use of both the TLB and CPU cache when possible. Adapted from here

Another good flowchart of how TLB works can be found on Wikipedia as well:

![Flowchart[5] shows the working of a translation lookaside buffer. For simplicity, the page-fault routine is not mentioned.](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/c/c1/Steps_In_a_Translation_Lookaside_Buffer.png)

Spatial Locality In Respect With TLB and Cache

Temporal locality refers to the behavior that if a piece of data is accessed, it is likely to be accessed repeatedly within a short timeframe. I think it is clear how TLB and cache gives computers a huge boost in performance. If we repeatedly access the same variable, its PTE would have an extremely high likelihood to be in the TLB so no address translations are required (meaning no pagewalk), and the value of the variable would have a high chance to be in cache and thus avoid requesting the data from the main memory. Both the PTE and cache saves a lot of CPU cycles and provides a noticeable increase in performance that programmers can exploit.

2a. Spatial Locality and TLB

So how does TLB benefit from spatial locality? Recall the quote that motivated this entire blog post stated that it is desirable for the memory needed by the page table to be placed close together in the VIRTUAL address space and disregards the location of the physical address. The reason for the disregard of the physical address has to do with the fact that the TLB caches the PTE and not the page itself. If data are close to each other such as the next element in the array, it is likely that the virtual address of the next element in the array to reside in the same virtual page and therefore has the same PTE. Meaning if two pieces of data reside in the same virtual page, then the only thing that differs is the offset and thus we can use the cached PTE from the TLB. A TLB hit allows us to avoid the page walk and thus avoid the overhead. Now let’s suppose we are accessing a ton of element in the array.

Speculation Without Any Evidence: In theory, as our page table is 4kB, then a single virtual page could (in our simplistic model) contain up to 1024 integers (4096/4 = 1024) but we know in reality it does not. Though this claim assumes we are running on a single core CPU as each core probably has their own TLB.

This would mean that when accessing 1024 integers stored sequentially, we will have 1024 TLB hits in a perfect world. This is an example of how TLB benefits from spatial locality.

- arr[0]: TLB Miss because we never accessed the array

- arr[1]: TLB hit because the page is big enough to be within the same page

- arr[2]: TLB hit because the page is big enough to be within the same page …

- arr[1024] or somewhere near there: TLB miss

Note: I should really get a old single-core CPU to test this claim. I have no evidence for this claim at all.

2b. Spatial Locality and CPU Cache

Recall that when when we have a cache miss, we will be required to travel to the distant land called the main memory (let’s assume that the page is present in the main memory). What we bring back from our travel is not the single desired piece of data (an integer in our example), but rather 64 bytes of data into the cache (this is a simplification). We can tell how big our cacheline is for the CPU on my system:

$ getconf LEVEL1_DCACHE_LINESIZE

64

This from my understanding should be placed into L1d cache. As mentioned earlier, in a perfect world, this would retrieve 16 integers into our cache. Therefore we can avoid travelling to the main memory when we access the first 16 integers in the array as the data should be stored into L1, L2, or L3 cache if we access them within a short time frame.

3. Expected Growth between TLB and Cache Miss When Iterating Through an Array Sequentially

Recall that in a perfect world, we should expect a TLB miss after the first 1024 elements and a cache miss after 16 integers. This means that we should see an extremely small amount of TLB miss but a large amount of cache miss. In other words, we should expect to see more TLB Hits compared to cache hits when accessing an array of elements.

Possible Methodology

Note: This is a proposed idea to test my idea but I have not done the experiment myself. I did try a bit on my modern laptop and I found it both hard to collect the right data and make any interpretation of the data I collected. This post was a random thought I had but has not evidence to back up my claim.

The following program will return the sum of the array accessed sequentially:

file: seq_sum.c

Code:

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <time.h>

#include "spatial_const.h"

int main() {

long sum = 0;

int *arr = malloc(sizeof(int)*size);

int *trash = malloc(sizeof(int)*size);

setup(arr, trash);

//hopefully the cache is now cold with garbage data

for (int i = 0; i < size; i++) {

sum += arr[i];

}

return sum;

}

where the size is determined by a global value size stored in the headerfile. setup just populates the array and tries to make the

cache to be cold by populating the cache hopefully with random values:

file: spatial_const.h

code:

#ifndef SPATIAL_CONST_H

#define SPATIAL_CONST_H

#include <time.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

int size = 1ULL<<20;

void setup(int *arr, int *trash) {

srand(time(NULL));

for (int i = 0; i < size; i++) {

arr[i] = rand() % size;

}

//attempt to make cache cold with garbage data

for (int i = 0; i < size; i++) {

trash[i] = i + rand() % size;

}

}

#endif

On my system, these are the available cores (though I wouldn’t want to use my multi-core system for this experiment):

CPU:

$ lscpu | grep -E "L[123].*cache"

L1d cache: 128 KiB (4 instances)

L1i cache: 128 KiB (4 instances)

L2 cache: 1 MiB (4 instances)

L3 cache: 6 MiB (1 instance)

The array has $2^20$ elements meaning it takes up 4GB which is way larger than what the cache can hold. Therefore, populating another random 4GB array should make the cache cold.

Based on my fiddling and some brief readings around the internet, I learned that it is very difficult to instrument your code properly with the proper metrics. As I do not have much background knowledge with this topic, if I was going to perform the experiment, I would be making assumptions and try to explain my findings that could be very flawed.

If I wasn’t lazy, we would be looking at the number of TLB data misses and L1 cache misses using perf with the following flags:

- dtlb_store_misses.stlb_hit: Stores that miss the DTLB and hit the STLB

- dTLB-load-misses

- dtlb_load_misses.miss_causes_a_walk: Load misses in all DTLB levels that cause page walks

- L1-dcache-load-misses

- l1d.replacement

We will have two programs: seq_base and seq_sum whose only difference is that the seq_base does not sum any numbers

As my CPU does not support L1-dcache-store-misses, I will be ignoring this counter entirely. The purpose of the base program is to get a

baseline of the counters that we can compare once we try to take the sum of the desired array.